When Anuška Delić left slovenian daily newspaper Delo and set up Oštro in 2018, she knew that Oštro would focus on her own strengths and experiences, investigative and data journalism, but also incorporate fact-checking, a role that she felt was missing from the media ecosystem in Slovenia.

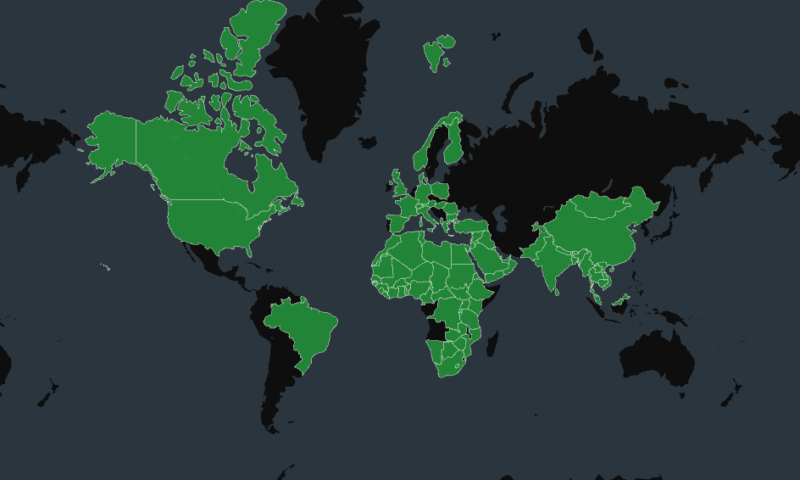

Anuška has extensive experience in cross-border investigations, having led the MEPs Project, which brought together journalists from EU member states to request information about the allowances of members of The European Parliament. She was also a member of global investigations including Panama Papers, Paradise Papers, and FinCEN Files.

So naturally the mission of Oštro is to nurture data and investigative journalism, safeguard the right to know, and spread journalistic knowledge and contribute to the training of future investigative reporters. Since its launch, the centre grew to a core team of seven journalists as well as six students working on paid placements for the fact-checking project.

Oštro is shaping the next generation of investigative journalists both in Slovenia and Croatia, through its sister centre and investigative collaborations, plugged into Anuška’s cross-border journalism contacts. I asked her about the process behind shaping the centre: how the trajectory of growth from fact-checker to investigative journalist is set out, and how their own code of conduct reflects their journalistic values and relationship with the public. The interview is edited for length.

Directory Editor: What is your process for training young journalists?

AD: We have an agreement with the Faculty of Social Sciences in Slovenia, which has the main journalism programme, so when students have this mandatory practice, they get a list of media and they can choose Oštro as well. Then we publish ads for students, and we have also received students who are not journalism students, which is great.

Just recently, in December, the fact-checking project got a new editorial leading duo, so a new editor and a new deputy editor. The editor before that was the deputy editor of the previous one. So we moved them up. They start with fact-checking, they learn, we see some want to do this, some don’t really find themselves in this kind of work. Some learn a lot, and then they go elsewhere. But mostly the people that stay, they then continue to develop.

And at one point we see that they are already showing a want, they’re fighting to find the truth. They are really internalising professional standards well, and they have a propensity for research. Then we start including them in investigations, and then they will continue learning to become investigative editors, so they can also do their own projects.

This is the way things work here. That’s also because we have next to zero human resources in investigative journalism in Slovenia. So we have to develop our own people.

Editor: How do you feel about Oštro’s growth since you started?

AD: The workload is always bigger than the team here, unfortunately, we would need to double ourselves to be able to do everything at a normal pace. Up until now, pretty much everything at Oštro was done by journalists. I had an assistant director who was helping out a little bit with the projects. In mid-November, we employed an actual project manager, she has 15 years experience and the last 10 years she was in a human rights NGO, and it’s just amazing what she’s doing and I’ve been sleeping so much better since then.

And the part-time communicator also came and we’re getting a student for social media, so a lot of things are now slowly and gradually being turned over from journalists to this new up-and-coming admin-communications team, which is amazing. I can’t even describe the feeling after five and a half years of doing everything ourselves. So it’s a hugely important moment for Oštro right now.

Editor: Did you grow organically or were you specifically looking to grow?

AD: Very much organically, but very much limited by the opportunities that we actually truly have from international donors. We are a small country, two million people, we are not particularly interesting to a lot of international organisations.

But somehow, we have managed to come to where we are today, but it was always driven by actual needs that were already gravely not being met – by the time we got to solving them, it was an emergency.

So we are now building our admin-comms team, but it would have been much better if we were able to start building it two years ago. That’s because of financial constraints, as it’s extremely hard to get core funding when you are from a small EU member country. We are getting project funding, which is great, but we all know that without core funding, we can’t really sustain our operations, we can’t continue to develop, and we can’t really do the work that we want to do, because we have to do projects to survive. So core funding is a hugely important thing right now for almost any non-profit journalism centre in EU member states.

Editor: I noticed that you subscribe to some of the already existing ethics codes, but you have also created your own. Why did you feel the need to do so? How is yours different?

AD: We did get a code fairly early on at Oštro. One reason is Oštro is radically transparent, so we wanted to also set up the principles of our work. We also set up some things that we found were really necessary in the environment we are working in: a very small country with a lot of interloping interests, and everyone is three steps away from the president. In my case, the current president of the country was the pro-bono lawyer of the MEPs Project when she was a lawyer, so it’s not even three steps away.

That’s why we felt it was necessary to deal in our code of conduct with actual and perceived conflict of interest, which we proactively disclose. So far we’ve only had cases of a perception of conflict of interest, we’ve never had a case of an actual conflict of interest, but we would proactively disclose those too.

We wanted to also explain the way we work with sources, because this is twofold. One, to explain to future sources how we work, two is to explain to the public: “look we’re actually taking journalism seriously, right?” Our investigations are based on primary documents, so that means that we don’t re-report the reporting of other media that we have no idea how they came up with. We publish verified information and we verify everything that we can.

All of these things, the alliance with the public, the corrections policies, non-profit operations, are not included in the national code of conduct of the Slovenian Association of Journalists, and so that’s why we felt the need to expand the principles, and apply them to what we do daily. And we change the code when we find new things that we should put in the code.

Editor: What do you mean by alliance with the public and how does that reflect in your work?

AD: At Oštro we believe in a two-way relationship with the public. This is another thing that is coming from my experience of working at Delo. There were a lot of readers’ letters, so there were ways for readers to prominently voice their opinions, but in a constructive way. And then that slowly, with the onset of social media and the trolls, perverted itself into these crazy comment sections below articles where people are just being nasty to each other and it’s actually fuelling hate speech in many cases.

I feel that the media has really shut out the public. The media wants something from the public, we want clicks and we want money, but we don’t want to give back. I think what we can give back is an attempt to have a constructive debate. So an alliance with the public means that we actually try to respond to people, emails, messages. If they are very nasty, we won’t, but even if they are a little nasty, we still will, because we try to have an open conversation.

And then what we also do is public editorial meetings that we actually hold literally outside, and we have mics so that people can hear there’s a conversation going, and we actively invite them to sit down and talk to us.

Editor: Where do you usually do them?

Anuška: For now we’ve done them in Ljubljana, one in a square and one in front of a bar neighbouring the town hall. Then just recently, in December, we held our first two public editorial meetings outside of Ljubljana. One was in Koper, on the seaside, and one was in Bled.

This is because we published a big investigation into the real estate market in the three most expensive areas, which is Ljubljana, the Alps, so around Bled, and then on the coast. We were trying to determine what share of newly built apartments, after 2015, is actually used for people to live in, and what is actually investments or tourism or Airbnb. So aside from doing an overall story, we also did three local stories, so we had public editorial meetings in the three cities.

At these meetings, either we have a project we just did and we want to talk about that, or we ask the participants if they see a story that we’re missing, or if they want to talk to us about the way our webpage works. Or sometimes we implant topics that we don’t tell them are about a future project, but we just want to talk about this topic.

It’s a very dynamic conversation and very open. The craziest thing happened actually in Ljubljana, somebody was participating throughout the entire meeting, asking really great questions. And then we finished and he’s like, “so what are you, like an institute or something”? So you don’t know who we are? He’s like, no, I saw it on Facebook.

We really believe that we need the public on our side, not just as Oštro. Journalism in general, because we’re losing ground as a profession. And I think without the public believing in us and trusting us, disinformation, propaganda and special interests will override any and all democratic debates. And we don’t want that. So it’s important that we honestly and constructively discuss things with the public when we can.