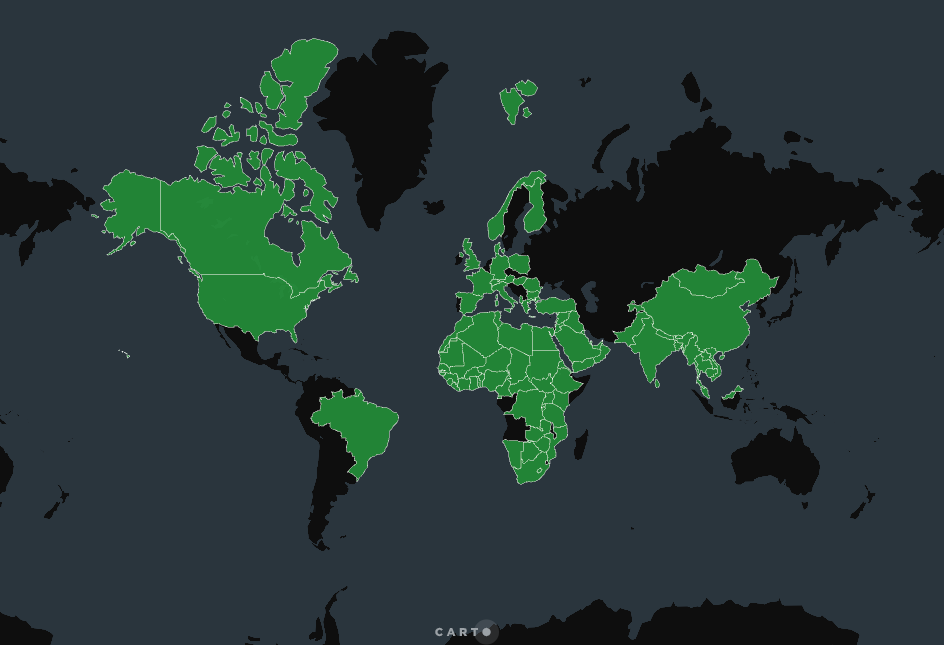

Founded in 2020, The Environmental Investigative Forum (EIF) now has 100 journalists in its network, working across 6 regional hubs covering 86 countries. Based in France, it was founded initially to draw replicable methodologies on the different investigation subjects the founders had worked on.

EIF then developed into a journalism consortium, focusing less on the experts and more on the journalists who were joining, although the forum retains a mix of expertise. The board and the advisory committee include organisations with a track record in environmental investigative journalism from the U.S., West Africa, Southern Africa, MENA and the Southeast Asia region. The team itself includes various journalists as well as an environmental expert and a remote sensing engineer, who help journalists apply satellite imagery analysis in their work.

The EIF network is free to join and is organised as a Signal group and a mailing list. Their focus is on cross-regional environmental investigations, aiming to go global with their work, and being mindful of the way their team members work with each other, avoiding some of the pitfalls of collaborative work their members have noticed in other contexts.

The EIF also led a global consultation about the challenges of investigative journalism focused on environmental issues, published in 2023, which advocates for the importance of cross-regional work and a better understanding and resourcing of environmental investigative journalism as a specialism.

To learn more about how they scope their investigations but also choose to work with each other, I asked co-founder and executive director Alexandre Brutelle to share more about the work and processes of EIF. The interview is edited for length.

Directory Editor: How does the EIF network function in practice?

Alexandre Brutelle: When someone is looking for a media partner, specific investigative technique, specific data, even some particular expertise, I will make the connection between various members or external media partners to support them in developing their investigations.

We do this in a non-predatory way, so we don’t have this huge network in order to use their investigation and call the freelancers our own. We only take part and credit for an investigation when we do participate directly in it, which might sound obvious, but not all organisations actually do that.

The network is supported by the team and the advisory members in order to develop new reporting tools, new ideas, share expertise, share contacts, advice, and support each other.

As an organisation itself, EIF does trainings and environmental monitoring tool development that can be used for investigative projects. So training, data tool development, mentoring supports, and of course, developing our own investigations.

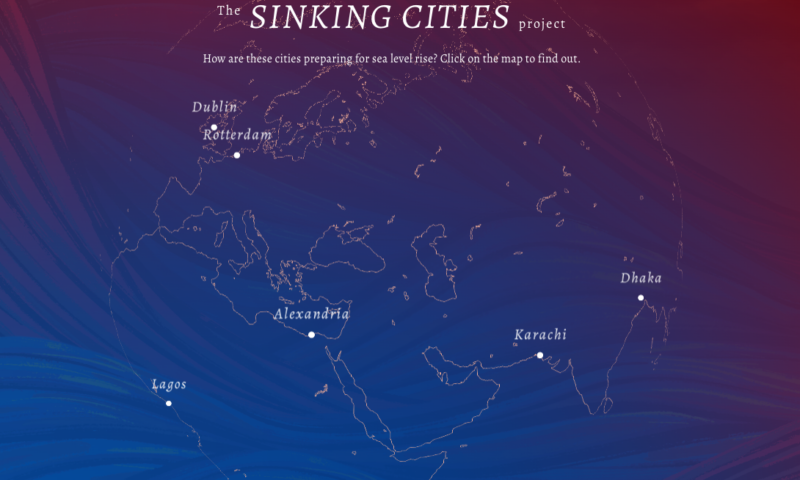

The latest is one that took us one year, about a company called Perenco, a company that we have investigated since 2020 on different occasions with different media partners. And for this last big project, we investigated environmental damage caused by the company worldwide. We published a three-chapter series of investigations and articles about the company in almost ten media outlets, in Tunisia, in Peru, in Brazil, in Cameroon, in Gabon, in France.

The investigative ideas come most of the time from the team, when it’s an EIF investigation. And the only investigations we do as EIF need to be either global or cross-regional. So more than one region. Not cross-border, but cross-regional.

Editor: What does cross-regional mean to your work and why choose cross-regional rather than cross-border? Is it a matter of language or is it a matter of how you look at the story?

AB: It’s really a matter of how to look at a story. With the Perenco company, we’ve been investigating for some time, we started working on Perenco in Tunisia (Perenco is the second largest oil and gas company in France, after Total, but it’s really less well known). And we started working in Tunisia and France already four years back. This went well, we had some good ideas, published it, then we moved the topic to DRC. We replicated it, we adjusted the idea to the country and to the extractive processes that are going on in that country, the type of impacts we could monitor etc, but then this would be endless.

We could have applied to one grant after another, Perenco being a global company, after working on Tunisia and DRC. But that would have meant applying each time to a Journalismfund Europe grant and taking some necessary space at each grant call.

That’s why we decided to now apply to grants and develop in-house investigations at EIF in one-go, to only focus on systemic issues and topics of investigation, with a cross-regional potential. As an example, when we took that decision, we said let’s keep on working on Perenco, but this time let’s do it on a global scale with the same methodology replicated in as many countries where Perenco is operating. And that’s what we did last December. And that’s what we’re going to keep on doing for several other topics that we started working on.

Editor: You grew now to over a hundred members. Are these the journalists who work with EIF regularly?

AB: Yes, but not as employees. Some of them we trained, some of them we give some tips to, others act as consultants or freelance journalists – it really depends.

Editor: How do you keep in touch with the members, do you get together occasionally and have these brainstorming sessions, or are the ideas for projects generated within a core group and then sent to the others to see who might want to get involved?

AB: We have both of these scenarios. The first one would be that the core team has an idea that can cover various regions at the same time, and we invest our own time to do some preliminary research and some tests with a hypothesis that we have. And if we see it’s a good basis for an investigation, and then for some story grant fundraising later, then we’re going to contact a few people and ask them if they want to be part of it.

What happens most of the time is that the journalists are going to want to apply on their own, and they’re going to ask us for some tips – how can I get this or that data. Sometimes they want us to review their application files, to help them phrase it better or they have some questions about some grants that we’ve applied to. So it ranges from support, to fundraising, to using a tool, finding data, finding contacts.

So far most of the stories that became EIF stories came from the core team, and then we connected with some members.

Editor: Returning to this idea about not being predatory with journalists, how do you see these issues happening elsewhere, and how do you address it?

AB: In the field of non-profit journalism, there’s a lot of profit, there’s a lot of financial flows that some organisations are counting on. And some of them are not going to be afraid to take some freelancers’ ideas, or some smaller organisations’ ideas and methodologies, and replicate them as their own.

We try not to do this. We try to really get involved with people and to have them as equal team members, not have token participants to projects and also the other way around, not kill the ideas. We’re going to keep them involved, if they come up with an idea.

If something goes bad, it goes bad for you, for your team members, and for the future of your work and your organisation.

Editor: What are some of the main challenges that you’re seeing now?

AB: If you start looking at which organisation is receiving financial support from some charities, foundations, you often end up seeing that accessing this funding is by invitation only.

I prefer to apply with our colleagues to open calls with an application process. And usually that turns out to go really well. But that makes it really hard to sustain the activity of an organisation, because you’re always running after the project. The difficulties and the challenges that a freelancer could get, always working different projects in parallel to make a living, but on the scale of an organisation.

And that really sucks, because we have some people in the network that are just consultants, volunteers, but that could really benefit from having a long-term position. While all the workload is going to be focused only on a few people that are okay to give their free time to EIF, that makes it hard.

Also the scarcity of the funding that’s available, not only for investigative journalism, but for investigative environmental journalism. You can see there are different scales of funding. And you can see that, by implication in a donor call or in some logic of financing by some foundations when it’s a closed call, there’s still this idea that there’s climate journalism on one end, and investigative journalism on another.

It’s still really hard to bridge the gap and that’s also what we try to do, we publish a report about that and also about the feelings from journalists and freelancers. Most of us have the feeling that there is a disconnect from the donors’ perspective between climate journalism and investigative journalism that should be bridged somehow, and that there are not enough funding opportunities for the journalist and also for organisations.