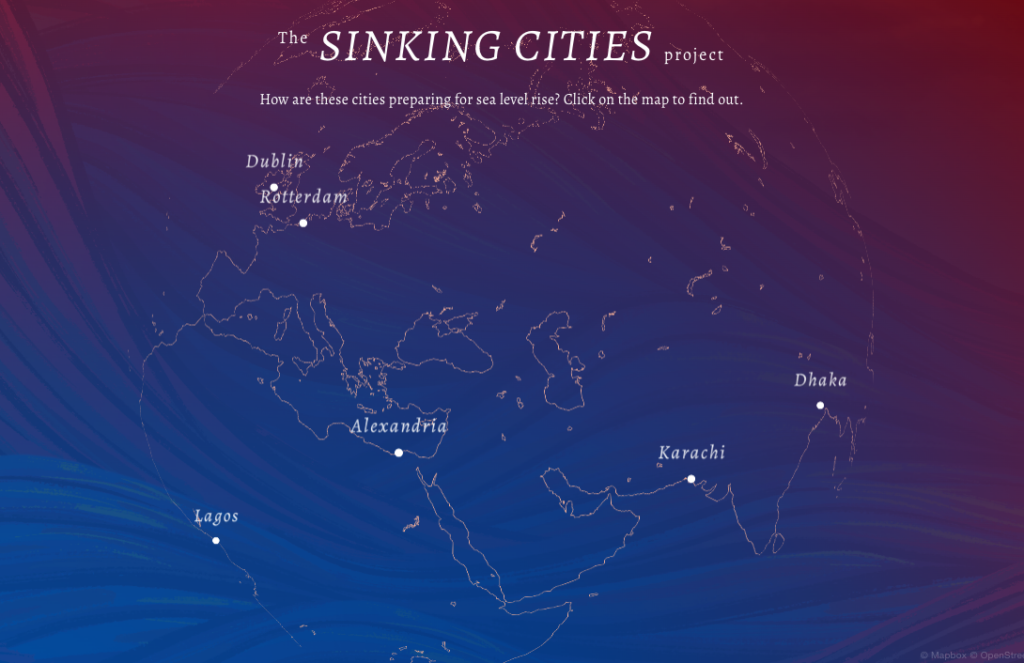

When a building on Miami’s coast collapsed on the beach in 2021, the Unbias the News team immediately thought of other cities with questionable real estate developments. Sharing stories from Lagos, Karachi and other places where building developers seemed to be ignoring the environment, they realised they had a great collaborative story on their hands.

They immediately came up with the idea for the Sinking Cities project, and they started work on it following the values of Unbias the News, the feminist cross-border newsroom managed by Hostwriter: working with local journalists from those cities where the story is happening, to document how local authorities are preparing for climate change, or whether they’re doing anything at all.

Through Sinking Cities, they covered environmental strategies in Dublin, Rotterdam, Lagos, Alexandria, Karachi and Dhaka, working with journalists who live in these cities, bringing them all together for trainings in order to complete a cross-border investigation that dove deep into the fabric of each city and how it’s seeing its future.

After publishing the project, they won the 2023 Climate Journalism Award by The European Journalism Centre. To unpack some of the goals and challenges of this award-winning project, I asked Unbias the News editor-in-chief, Tina Lee, about their work. The interview is edited for length.

Directory Editor: How did you start the Sinking Cities project?

Tina Lee: We thought it was such a good idea that before we had even secured funding, we immediately put something out because we were sure that somebody would have that idea sooner or later.

Something we’ve noticed in climate journalism is that there is a great deal of very innovative journalism being done, but it’s often done by people that don’t live in that country. And they fly to places. They do an amazing story with beautiful videos or graphs, and then it’s read by the audience for the newspaper, but it’s not necessarily read by the people in the place they cover.

What can be lost when that happens is that you don’t necessarily name names. You don’t know the local context. So you talk about the country in general or the city in general, but you might not get into the really specific things about political parties. And one thing that we thought was important is that the public knows who to put the blame on when things go wrong, or who to reward when things go right. So we thought it would be good to really get very local.

With high-level climate change stories, there’s not a lot of local journalists out there that have been doing them. We also wanted to offer this chance to train them so that they become go to people in their cities.

Editor: What steps did you have between the idea and publication? How did the training work?

TL: We announced that we were going to do it, so then the next step was to try to secure funding – it was partially funded by JournalismFund. One of the things that we wanted to do is make sure that this was paid really well, because we wanted the people who did it to dedicate some time to working in a cohort and getting this training.

And we also wanted them to get what they would get if they worked for a big magazine. Because one of the other problems with this kind of journalism is that you have really high expectations for what people are going to do. And then you pay them $1,000 for six months of work.

So we wanted to make it a big enough commission that it was competitive, that people really wanted to do it, but that they would feel really comfortable spending quite some time on this. So the payment was €4,500 per person, which I think is not that normal for a big written piece.

What we were especially looking for was people who had a local understanding of the issues. Not necessarily someone who had climate expertise, but someone who was passionate about telling what was happening to their community.

And once we got them together, our idea was mainly that they have meetings with us occasionally, that they also meet with each other. A lot of people had similar things going on in the different cities, but what we also wanted was everybody to know what are the country obligations that they’ve made to international bodies, all the promises that have been made on behalf of the city. To really read through the legal texts, be aware of what is the best, most reliable science on the topic for each country. We wanted the status quo.

Later on, as the project continued, we asked for an expert climate journalist to give us where he finds sources, his tips and tricks, how he gets people to reply to him when he writes emails.

One of the biggest issues that up and coming journalists face is that people don’t reply to their emails. I’m not sure if people are aware of this at the high levels of journalism, but just the fact that people, government, ministries just don’t respond. So that was something we asked. He had some good tips for that. One was to not contact the academic you want directly, but contact the university press office. So that they’ll encourage the people, because they are much more eager for their university to be in the press.

We had a couple of different trainings, they had to also present to each other. What happened is that we started learning all these typical issues that are going on with sea level rise, such as the issues of saltwater incursion and groundwater contamination and what kind of barriers make sense and don’t make sense, and how marshlands protect or don’t protect.

They could see which things were similar, which things were different. So, it was also good for comparing „how unusual is what’s happening in my city?”.

Editor: The design is very complementary, with different maps with what the areas used to look like, and how they look after buildings were completed. Who pitched in?

TL: That one particularly for Lagos was a very interesting one because in some of the other cases, there was information available. But in this case, there actually wasn’t.

So Ope Adetayo, who is very innovative, dug in and came to the conclusion that it would be actually impossible to tell this story without having more climate data.

So we had some funds available for freedom of information act requests, trying to get that kind of data. And he’s like, “Tina, the Nigerian government is not responding. And they actually told me they don’t even have this data.” So we actually commissioned satellite data ourselves. And that’s what that is, in the story. We have better information about that topic then I think a lot of academics do.

We actually now have better data available, because we were just able to use the satellite imagery. And we hired Mansir Muhammed, OSINT specialist at HumAngle, they worked together to also highlight how much the marshland has been eaten into and how much real estate development has gotten there.

Editor: What were some of the other challenges of the project?

TL: There’s always cultural challenges, the fact that people will have different relations to deadlines. And also, in the different places that we looked at, we had some minor security concerns because criticising your government is more okay in some places than others.

And also the fact that it was really difficult for us to get answers from the government. Especially when it comes to huge real estate deals and real estate investment. We wanted to know what kind of environmental impact assessments they had made. And governments were really not forthcoming about that information, although it should be public.

Editor: What was your desired impact?

TL: We had several. Number one is that we wanted to show that local climate journalists can do just the bang-up job of doing an in-depth climate investigation as legacy media top-notch reporters can. That goal I believe that we accomplished.

All of them have received awards, have been invited to present the findings at conferences, have had new opportunities arise after participating.

Part of that is also that we wanted to diversify climate journalism. Climate journalism is very first world. It’s very white. When you do stories about climate in the Global South or the global majority, it’s shown as a natural force without politics. And in the Global North, it’s more about money and corruption. We wanted to show that you could do those kinds of stories too, if you actually hire people that live in those places and know how to do it.

And we wanted to also try to have different voices, especially expert voices, because even when there is climate reporting that’s done about different countries, often the experts that are quoted are people from the Global North. Especially men, white men from the United States and Europe. So we wanted to showcase a different thing.

A lot of it was about trying to prove our points. Unbias the News exists to give opportunities to journalists who face structural barriers. So this was a really ambitious chance to show that there’s really no need to duplicate the structural barriers in doing climate reporting.

You can do climate reporting in a collaborative way. You can do it in a way that offers chances to up and coming young journalists, local journalists.

What we also wanted to test was our open source journalism prototyping, which is that we have a network, the Indie Newsroom Alliance, and the idea is that people from the alliance can publish any of our stories for free. And we knew that in some countries, to do a big in-depth report like that would be difficult to afford, especially cross-border, so being able to then get back into those newspapers the other way, from us, meant that the locals living in those places could read it. Because let’s face it, not everybody reads Unbias the News, right? We’re a Germany-based place, we do international reporting but it’s not like we’re mega famous. But if you were in Lagos you probably saw this report, it was in 18 different newspapers in Nigeria.

Unbias the News is supported by Hostwriter, an organisation powering collaborative journalism. You can access several Tip Sheets from Hostwriter ambassadors for free online, as well as two booklets about cross-border journalism as a method, and as a mindset.